DE EERSTE FEMINIST (?) DEEL 1

- HWP x Matilda's Diaries

- 24 feb 2025

- 13 minuten om te lezen

Bijgewerkt op: 1 jan

Christine de Pizan (ca. 1364-1430) wordt beschouwd als een van de eerste deelnemers aan het zogenaamde 'querelle des femmes'. Dat geeft haar een buitengewone positie in onze geschiedenis. Tenminste, dat zou je denken. De Pizan is nog steeds niet opgenomen in historische of filosofische canons. Want zowel historici als filosofen debateren of we De Pizan wel kunnen betitelen als feminist en/of als filosoof.

Wanneer feminisme ter sprake komt, denken velen aan de strijd voor de emancipatie van vrouwen, die zich sinds 1850 in verschillende ‘golven’ heeft afgespeeld. Maar veel eerder dan dat vond er een brede internationale discussie plaats over de aard van vrouwen en of zij konden studeren, schrijven en regeren zoals mannen. Deze discussie wordt de querelle des femmes genoemd, de ‘vraag van de vrouwen’, en vond wereldwijd plaats tussen ongeveer 1400 en 1700. Christine de Pizan wordt beschouwd als een van de eerste deelnemers aan deze discussie – zo niet de eerste. Maar is ze met haar opmerkelijke positie binnen de geschiedenis te betitelen als een feminist, een filosoof, of misschien wel als allebei?

Christine de Pizan: de feminist (?)

Christine werd rond 1364 geboren in de Republiek Venetië als Christine da Pizzano. Haar vader werkte als astroloog, arts en adviseur aan het hof van de Republiek. Toen Christine vier jaar oud was, nam hij een positie aan het hof van de Franse koning Karel V. Christine en de rest van de familie volgden enkele jaren later. Haar positie aan het Franse hof, verzekerde Christine, ook al was ze een meisje, van een gedegen onderwijs. Op 15-jarige leeftijd trouwde ze met de koninklijke notaris Etienne du Castel, en kreeg drie kinderen met hem – een van hen stierf jong, een dochter werd uiteindelijk non.

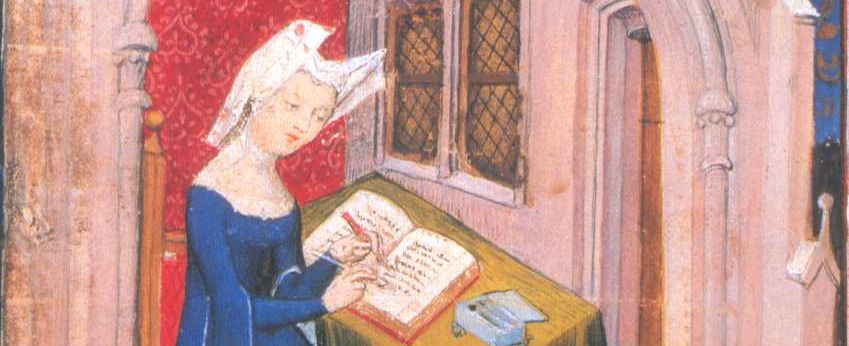

Net als veel andere historische vrouwen die schreven, bevond Christine de Pizan zich in een uitzonderlijke positie die haar ertoe bracht een carrière van het schrijven te maken. Christine’s vader overleed in 1388 en haar man stierf in 1389 aan de pest. Christine had moeite om toegang te krijgen tot de nalatenschap van haar man en de lonen die nog aan hem verschuldigd waren. Daarom werd zij een professionele schrijfster. Ze begon als kopiist van manuscripten en ging vervolgens haar eigen werken schrijven, die aanvankelijk bestonden uit liefdesballades die de aandacht trokken van rijke beschermheren – het was een tijd waarin de rijken boeken bestelden bij getalenteerde schrijvers. Christine begon snel te werken voor Franse edelen, zoals Isabeau van Beieren, Lodewijk I, hertog van Orléans, en Marie van Berry. Ze wijdde haar tijd aan het schrijven over politiek en staatsmanschap. Daarmee was ze, voor zover bekend, de eerste vrouwelijke schrijver die haar brood kon verdienen met haar beroep.

In 1402 begon ze de werken te publiceren waarvoor ze het meest bekend zou worden. In een pamflet stelde ze de literaire waarde van de veelgelezen roman Roman de la Rose in twijfel. Dit enorm populaire boek, dat meer dan een eeuw voor Christine’s tijd werd gepubliceerd, satiriseerde de conventies van de hofliefde, maar stelde vrouwen ook voor als niets anders dan verleidsters. Christine vond dat deze visie kortzichtig was. Drie jaar later publiceerde ze Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (Het Boek van de Stad der Vrouwen). Met dit boek ging ze verder dan haar initiële kritiek en zocht ze de deugden en capaciteiten van vrouwen te benadrukken. In drie delen bouwde ze de fundamenten van een stad van dames (en het boek zelf) door bekende historische, bijbelse en mythologische vrouwen te beschrijven. Stuk voor stuk vormen zij argumenten voor de visie van de Pizan dat vrouwen een actieve rol zouden moeten spelen in de middeleeuwse samenleving en dat er gelijkheid tussen mannen en vrouwen zou moeten zijn in het onderwijs.

In hetzelfde jaar publiceerde de Pizan ook Le Livre des Trois Vertus (Het Boek van de Drie Deugden), waarin zij lessen gaf aan vrouwen uit alle lagen van de bevolking om hen deugdzamer te maken. Christine wijdde het boek aan de dauphine, Margaretha van Nevers. Het was een speciaal handboek voor haar over hoe zij zich hoorde te gedragen.

"If it were customary to send little girls to school and teach them the same subjects as are taught to boys, they would learn just as fully and would understand the subtleties of all arts and sciences" - Christine de Pizan

De Pizan zette in de meeste van haar werken mysoginie en de verdediging van haar geslacht tegen onredelijke beschuldigingen centraal. Voor zover bekend, werd Christine de Pizan daarmee de eerste schrijfster die systematisch westers seksisme aankaartte. Filosofe Joyce Pijnenburg vertaalde als eerste enkele van De Pizans teksten naar het Nederlands voor haar boek Pen, bed en habijt (2021). Daarin stelt zij ook dat de overtuigingen en standpunten van De Pizan als feminisme kunnen worden betiteld. De schrijfster herkende het seksisme van haar tijd en verzette zich ertegen. Vrouwenhistorica Els Kloek zegt daarentegen in haar boekje Feminisme (2024) (uit de serie Elementaire Deeltjes) dat het niet juist zou zijn om De Pizan het predicaat 'eerste feministe' te geven. Ze was dan wel iemand die nadacht over de scheve verhoudingen tussen mannen en vrouwen, maar ze zou ook een kind van haar tijd zijn geweest. Kloek vindt dat De Pizan teveel nadruk legt op vrouwelijke deugdzaamheid en te weinig zegt over de daadwerkelijke verandering van man-vrouwrelaties om als feminist te kunnen worden gezien.

Daarbij moet wel gelet worden dat Pijnenburg en Kloek verschillende definities van het feminisme hanteren. Pijnenburg definieert het als het opmerken van en het opstaan tegen seksisme - discriminatie op basis van sekse- en genderverschillen. Kloek kiest voor de historische benadering van het feminisme, zoals verwoord door Karen Offen: de kritische reactie op het welbewust en systematisch ondergeschikt houden van vrouwen door mannen binnen een gegeven culturele context. Beide zijn echter enge definities van feminisme en sluiten vele doeleinden van het feminisme per definitie uit. In zijn boek Feminisme voor mannen en andere wezens (2023) betoogt filosoof Frank Meesters voor een zo breed en vaag mogelijke definitie van het feminisme. Juist omdat de term zoveel behelst. Het zou interessant zijn om te onderzoeken of De Pizan volgens zijn theorie wel (of niet) een feminist genoemd kan worden.

Tegelijkertijd kunnen we onszelf afvragen of het wel zo belangrijk is om te twisten over de labels die we op De Pizan kunnen plakken. Hoewel ze de genderrollen van haar tijd als natuurlijk zag, kwam De Pizan wel op voor de onafhankelijkheid, het respect en de veiligheid van vrouwen. Dat betekent dat De Pizan en feministen toch echt wel aan dezelfde kant staan en dat het moderne feminisme op zijn minst op haar schouders staat.

Christine de Pizan: de filosoof (?)

Niet alleen werken waarin De Pizan nadacht over genderrollen kleurden haar oeuvre. Ze schreef over velerlei onderwerpen in allerlei genres, zo ook over religie, politiek, macht, staatsmanschap en oorlog. Dit kwam grotendeels door haar klantenkring en de tijdsgeest. Aan het begin van de 15e eeuw, door hofintriges en opvolgingscrises, werd Frankrijk in een burgeroorlog gestort en bevond het zich opnieuw in militaire conflicten met Engeland als onderdeel van de Honderdjarige Oorlog. In deze omstandigheden schreef Christine werken over oorlogvoering, vrede, de realiteit van conflicten, evenals een boek specifiek voor de jonge Dauphin over hoe te regeren.

De Pizan wordt echter minder (h)erkend om haar religieuze, politieke en filosofische traktaten, zoals Enseignements moraux (Morele Lessen uit 1395), L'Épistre au Dieu d'amours (Epistel aan de god van liefde uit 1399), Livre du corps de policie (Boek van het politieke lichaam uit 1407) en Livre de paix (Boek van vrede uit 1413). Ondanks het feit dat ze beroemd was in haar eigen tijd en ze zichzelf als filosofe zag, wordt ze zelden in moderne filosofische canons opgenomen. Vele mannelijke collega's zouden op soortgelijke manier na haar schrijven over dezelfde onderwerpen: Niccolò Macchiavelli in Il Principe (1532), Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651), Carl von Clausewitz in Vom Kriege (1832), en de lijst gaat door. De Pizan werd dan wel genoemd als vrouwelijke filosofische pionier in een artikel van Filosofie Magazine uit 2014. Maar anno 2024 bewenen Italiaanse filosofen Chiara Bottici en Antonella Buono dat ze nog steeds door hun discipline wordt onderschat.

Bottici is van mening dat De Pizans geslacht te maken heeft met het gebrek aan erkenning. Het artikel 'Diversiteit als toetje' van filosofie docenten Heleen Booy en Kiki Varenkamp, waarin zij illustreren dat filosofie nog steeds door mannelijke figuren wordt gedomineerd, ondersteund dat. Maar in Buono's interessante promotieonderzoek stelt de Italiaanse filosofe dat Le Livre de la Cité des Dames een fundamentele tekst is binnen de feministische filosofie. Buono heeft het boek geïdentificeerd als een metafysisch discours waarin de kwestie omtrent de inferioriteit van vrouwen worden onderworpen aan logische en rationele inspectie. Wordt De Pizan niet als filosoof gezien, omdat ze zich (als eerste) aan feministische filosofie waagde? Is feministische filosofie minderwaardig in de mannenafdeling die de filosofie nog veelal is? Of gaan feminisme en filosofie hand in hand?

Nadat De Pizan de laatste 10 jaar van haar leven in een klooster had gespendeerd, wegens de overname van Parijs door de Engelsen, kwam zij rond 1430 te overlijden. Haar werk werd na haar dood nog eeuwenlang genoemd, gekopieerd en vertaald. Tegen het begin van de 19e eeuw werd haar werk niet meer gepubliceerd in Frankrijk en raakte haar naam in de vergetelheid. Het werd echter weer nieuw leven ingeblazen aan het begin van de 20e eeuw door Mathilde Laigle en Marie-Josephe Pinet, die opmerkte dat niemand in Frankrijk aandacht aan haar schonk, maar dat zij nog steeds werd genoemd in traktaten in naburige landen. Vervolgens zou de feministische beweging van de 20e eeuw De Pizan omarmen. Simone de Beauvoir noemt haar de eerste vrouw die haar pen oppakte om haar geslacht te verdedigen. Is de omarming door het moderne feminisme wellicht een probleem voor de filosofie?

Het academische debat over de vraag of het werk van de Pizan als feministisch en/of als filosofisch kan worden beschouwd is nog steeds gaande, zonder definitieve conclusies over welke boxjes we kunnen aanvinken.

De auteurs hebben van de volgende boeken gebruik gemaakt bij het schrijven van dit artikel. In de tekst zelf wordt door middel van links verwezen naar gebruikte tijdschrift- en kranten artikelen.

Dit artikel maakt deel uit van een samenwerking tussen het Historical Women Project en Matildas Diaries.

Matildas Diaries is een Engelstalig platform, genoemd naar het 'Matilda Effect', het fenomeen waarbij de prestaties van historische vrouwen vaak overschaduwd worden. Matildas Diaries maakt video's over vrouwelijke pioniers die herinnerd moeten worden voor hun uitvindingen, daden en prestaties.

Over ons verhaal rond Christine de Pizan, maakte Matildas Diaries een prachtige animatie!

- ENGLISH BELOW -

Christine de Pizan (c. 1364-1430) is considered one of the first participants in the so-called 'querelle des femmes'. This gives her an extraordinary position in our history. At least, you would think so. But both historians and philosophers debate whether we can label de Pizan as a feminist and/or a philosopher.

When feminism comes up in conversation, many think of the struggle for women's emancipation, which has unfolded in various ‘waves’ since 1850. However, much earlier than that, there was a broad international discussion about the nature of women and whether they could study, write, and govern like men. This discussion is called the querelle des femmes, the ‘question of women’, and it took place globally between approximately 1400 and 1700. Christine de Pizan is considered one of the first participants in this debate—if not the very first. But should her remarkable position in history label her a feminist, a philosopher, or perhaps both?

Christine de Pizan: The Feminist (?)

Christine was born around 1364 in the Republic of Venice as Christine da Pizzano. Her father worked as an astrologer, physician, and advisor at the court of the Republic. When Christine was four years old, he took a position at the court of King Charles V of France. Christine and the rest of the family followed a few years later. Her position at the French court, Christine insisted, ensured her a solid education, even though she was a girl. At the age of 15, she married the royal notary Étienne du Castel, with whom she had three children—one of whom died young, and a daughter eventually became a nun.

Like many other historical women who wrote, Christine de Pizan found herself in an exceptional position that led her to pursue a career in writing. Christine’s father died in 1388, and her husband passed away in 1389 from the plague. Christine struggled to gain access to her husband’s inheritance and the wages still owed to him. As a result, she became a professional writer. She began as a manuscript copyist and later started writing her own works, initially producing love ballads that attracted the attention of wealthy patrons—this was a time when the rich commissioned books from talented writers. Christine quickly began working for French nobility, such as Isabeau of Bavaria, Louis I, Duke of Orléans, and Marie of Berry. She dedicated her time to writing about politics and statesmanship, thus becoming, as far as is known, the first female writer who could earn her living through her profession.

In 1402, she began publishing the works for which she would become most famous. In a pamphlet, she questioned the literary value of the widely read novel Roman de la Rose. This immensely popular book, published more than a century before Christine’s time, satirized the conventions of courtly love but also portrayed women as nothing more than seductresses. Christine felt this view was short-sighted. Three years later, she published Le Livre de la Cité des Dames (The Book of the City of Ladies). With this book, she went beyond her initial criticism and sought to emphasize the virtues and capabilities of women. In three parts, she built the foundations of a city of ladies (and the book itself) by describing well-known historical, biblical, and mythological women. One by one, they formed arguments for Christine’s view that women should play an active role in medieval society and that there should be equality between men and women in education.

In the same year, de Pizan also published Le Livre des Trois Vertus (The Book of the Three Virtues), in which she offered lessons to women from all walks of life to make them more virtuous. Christine dedicated the book to the dauphine, Margaret of Nevers. It was a special manual for her on how she should conduct herself.

"If it were customary to send little girls to school and teach them the same subjects as are taught to boys, they would learn just as fully and would understand the subtleties of all arts and sciences." — Christine de Pizan

In most of her works, de Pizan focused on misogyny and the defense of her gender against unreasonable accusations. As far as is known, Christine de Pizan became the first writer to systematically address Western sexism. Philosopher Joyce Pijnenburg was the first to translate some of de Pizan’s texts into Dutch for her book Pen, Bed en Habijt (2021). In that book, she argues that de Pizan’s beliefs and views can be considered feminist. The writer recognized the sexism of her time and opposed it. However, women’s historian Els Kloek argues in her book Feminisme (2024) (from the Elementaire Deeltjes series) that it would not be accurate to label de Pizan the ‘first feminist.’ While she did think critically about the imbalanced relations between men and women, she would have also been a child of her time. Kloek believes that de Pizan places too much emphasis on female virtue and says too little about the actual change in male-female relationships to be considered a feminist.

It should be noted, however, that Pijnenburg and Kloek use different definitions of feminism. Pijnenburg defines it as noticing and standing up against sexism—discrimination based on gender and sex differences. Kloek opts for the historical approach to feminism, as expressed by Karen Offen: a critical reaction to the conscious and systematic subordination of women by men within a given cultural context. Both are narrow definitions of feminism and, by definition, exclude many aims of feminism. In his book Feminisme voor mannen en andere wezens (2023), philosopher Frank Meesters argues for as broad and vague a definition of feminism as possible, precisely because the term encompasses so much. It would be interesting to explore whether, according to his theory, de Pizan could (or could not) be considered a feminist.

At the same time, we may ask ourselves if it is really so important to argue over the labels we assign to De Pizan. Although she saw the gender roles of her time as natural, De Pizan did stand up for the independence, respect, and safety of women. That does mean that De Pizan and feminists are on the same side, and that modern feminism stands on her shoulders amonst many others.

Christine de Pizan: The Philosopher (?)

Not only works in which de Pizan reflected on gender roles colored her oeuvre. She wrote on many different subjects in various genres, including religion, politics, power, statesmanship, and war. This was largely due to her clientele and the spirit of the times. At the beginning of the 15th century, due to court intrigues and succession crises, France was plunged into a civil war and found itself once again in military conflicts with England as part of the Hundred Years' War. Under these circumstances, Christine wrote works on warfare, peace, the reality of conflicts, as well as a book specifically for the young Dauphin on how to govern.

However, de Pizan is less (recognized) for her religious, political, and philosophical treatises, such as Enseignements moraux (Moral Teachings, 1395), L'Épistre au Dieu d'amours (Epistle to the God of Love, 1399), Livre du corps de policie (Book of the Political Body, 1407), and Livre de paix (Book of Peace, 1413). Despite being famous in her time and seeing herself as a philosopher, she is rarely included in modern philosophical canons. Many male colleagues would later write on similar subjects: Niccolò Machiavelli in Il Principe (1532), Thomas Hobbes in Leviathan (1651), Carl von Clausewitz in Vom Kriege (1832), and the list goes on. De Pizan was mentioned as a female philosophical pioneer in an article by Filosofie Magazine in 2014. Yet, as of 2024, Italian philosophers Chiara Bottici and Antonella Buono lament that she is still underappreciated in their discipline.

Bottici believes that de Pizan’s gender has something to do with the lack of recognition. The article Diversiteit als toetje by philosophy teachers Heleen Booy and Kiki Varenkamp, which illustrates that philosophy is still dominated by male figures, supports this view. But in Buono's fascinating doctoral research, the Italian philosopher argues that Le Livre de la Cité des Dames is a fundamental text in feminist philosophy. Buono has identified the book as a metaphysical discourse in which the question of women’s inferiority is subjected to logical and rational scrutiny. Is de Pizan not seen as a philosopher because she was (the first) to engage with feminist philosophy? Is feminist philosophy considered inferior in the male-dominated field that philosophy still largely is? Or do feminism and philosophy go hand in hand?

After spending the last 10 years of her life in a convent due to the English occupation of Paris, de Pizan died around 1430. Her work continued to be mentioned, copied, and translated for centuries after her death. By the beginning of the 19th century, her work was no longer being published in France, and her name faded into obscurity. However, it was revived at the start of the 20th century by Mathilde Laigle and Marie-Josephe Pinet, who noted that while no one in France paid attention to her, she was still cited in treatises in neighboring countries. Then, the feminist movement of the 20th century embraced de Pizan. Simone de Beauvoir called her the first woman to take up her pen to defend her gender. Is this embrace by modern feminism perhaps a problem for philosophy?

The academic debate on whether de Pizan’s work can be considered feminist and/or philosophical is still ongoing, with no definitive conclusions about which boxes we can check.

The authors have used these titles to write this article. Magazine articles are referred to with links in the text.

This article is part of a collaboration between Historical Women Project and Matilda's Diaries.

Matilda's Diaries is an English-language platform, named after the 'Matilda Effect', the phenomenon that tends to overshadow the achievements of historical women. Matilda's Diaries creates videos about women pioneers that need to be remembered for their inventions, acts and deeds. They made a beautiful animation about our story on Christine de Pizan!

Opmerkingen